Over the past five or six years, I’ve found myself surrounded by friends who have a love for the art of film. We hit the spectrum on what we see and enjoy. We’re there for a lot of the franchise films – the Marvels and Star Warses – but particularly enjoy the smaller films (call them independent, artsy, whatever you will). A few of us gather for a weekly movie night where choose a film in a selected theme in an effort to see films that might have otherwise been overlooked.

Regardless, going to the theater or watching in one of our homes, film is a communal event for us, and the conversation we have post-movie is really what watching movies is about for me. Film is a gift.

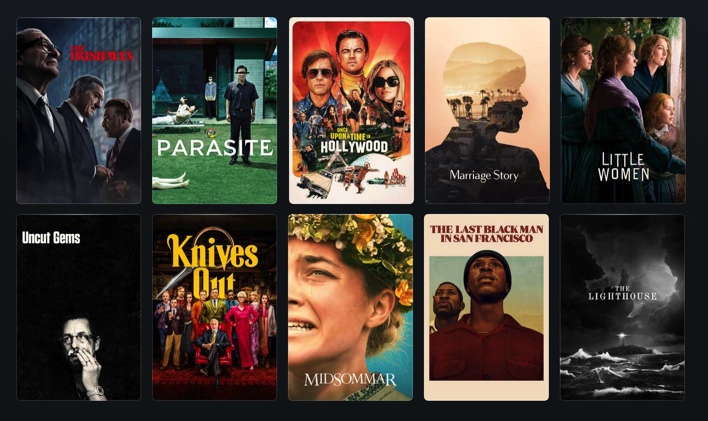

2019 has been a rich year in film, or maybe it feels so because last year’s films didn’t resonate with me outside a few brilliant takes (Roma, BlacKkKlansman, If Beale Street Could Talk). So instead of merely putting out a Top 10 for this year, I wanted to take a deeper perspective in what I consider the top 10 best films of the year. What themes appear? What does that say about the year in film, and more importantly, what does that mean I’m connecting with? So without further introduction, here is my Top 10 list for film:

- The Irishman (Martin Scorsese)

- Parasite (Bong Joon-ho)

- Once Upon a Time in … Hollywood (Quentin Tarantino)

- Marriage Story (Noah Baumbach)

- Little Women (Greta Gerwig)

- Uncut Gems (Josh Safdie & Benny Safdie)

- Knives Out (Rian Johnson)

- Midsommar (Ari Aster)

- The Last Black Man in San Fransisco (Joe Talbot)

- The Lighthouse (Robert Eggers)

The Ugliness of Capitalism

When I think on my list, no theme runs deeper than what I can only call anti-capitalism (and in some cases, anti-rich). Film often tends to be a commentary of the time in which it was made, and thus it is not surprising to see this narrative prevalent in our films this year. There are even a few “honorable mentions” from 2019 that did not make my Top 10 that likewise share in this sentiment (particularly Hustlers and Joker). Some films make this theme explicit, such as Parasite, which features on a working-class family, the Kims, who con their way into individual serving roles for the same wealthy family, the Parks. While the rich family is away on a camping trip for their son’s birthday, the Kims manage to have a vacation of sorts in this house. Not all is as it seems, as they soon realize that those they conned out of work for their own employment – fellow citizens who likewise look for work as drivers and housekeepers – have been living in a secret room in the basement and smuggling food at night. Despite living in what is essentially a concrete room, it is still better than the ruins of the city where we see the Kim family reside. When Parasite focuses on the Parks, it is often with a veiled contempt for their employees. While pleasant in the presence of the Kims, the Parks often criticize their workers’ appearance or demeanor. Of particular significance is the Mr. Kim’s odor, a running commentary through the film which has a significant payoff in the film’s climax. Greed and class discrimination play a pivotal role in the conflict that arises and the statement that this film ultimately wants to make.

Likewise, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, focuses on class separation, though in a much more personal and grounded story. Small in scale and perspective, this film transcends just these few characters and this particular city, the themes of gentrification and the illusion of progress impact many in cities across the country, including my home of Denver. Progress is typically marked as shiny new buildings and affluent new residents. Yet this new visibility can come at the expense of those who have called the many blocks and neighborhoods that comprise a city their home. Thus is the narrative in Last Black Man, where a younger man, Jimmie, wants to care for the house his grandfather supposedly built. The fact that Jimmie’s family no longer owns the house is irrelevant to him. The house is his family history and it is now lived in by strangers, not only to the house, but to San Francisco itself. There are subtle takes about poverty that comprise the essence of this film. Of note is the scenes Jimmie and his friend Mont skateboard around the city as a means of transportation, a literal uphill battle given the landscape of San Fransisco. If one cannot afford a car or bus travel, getting between points A & B are exceptionally difficult.

Uncut Gems and Knives Out provide subtler commentaries on this theme, but are no less poignant. In Uncut Gems, Adam Sandler’s Howard is a New York City jeweler constantly trying to make it rich. The problems that face him are multitude, but perhaps none greater than his own misdeeds and addictions to scheming the system. The rules of this story are what I can only imagine are the underbelly of capitalism. We all want to be rich, and here we see people begging, borrowing, and stealing to make it rich. It’s a dark, nearly futile world, and Howard resigns himself to it despite some small windows of opportunity to escape it and still live comfortably.

In Rian Johnson’s Knives Out, we get a lively, fun, and at-times subversive take at a murder mystery story. Here, we see the story of a wealthy family who comes together to celebrate its patriarch’s birthday, only for him to be killed that night. In a surprise to his entire family, the house and family fortune are not divided amongst all the children, but instead left entirely to the caregiver, Marta. What transpires is an examination of how and potentially who killed the father, all while the family attempts to con Marta out of her inheritance. I want to stop any synopsis there, at risk of giving any further plot or clue away to this brilliant film’s ending. However, viewers should subtly look at the end at the physical location of Marta and the family in the film’s final shot, a culmination of a subtle commentary of the rich versus poor that speaks loudly in this film.

Even Little Women, Greta Gerwig’s magnificent new adaptation of the Louisa May Alcott novel, has moments of explicit commentary on how a capitalist system only benefits from. With a historical perspective, Gerwig has one of the March sisters, Amy, confront the reality of marriage. For women, her specifically, marriage can be a form of economic prosperity, but only if marrying rich. However, for a woman at the time, any assets she would have had would have become her husbands at the moment they became married. Amy is not disillusioned or untethered from this reality, and makes it clear she will choose love, but must be tactical in who she partners so that she can will her best possible future.

Reflection & Contemplation

Reflection is deeply personal, which makes the translation of a fictitious character’s own reflection to a wide audience via the screen a challenging endeavor. This year offered a bounty of films which accomplished this successfully, and through a diverse set of perspectives.

Making Scorsese’s The Irishman, offered the greatest surprise in this regard. Scorsese has long been one of my favorite filmmakers. His art in the craft has always challenged me. His nuance in small moments of his films often play pivotal roles, which invites me to immerse myself in the world he is creating. With The Irishman, I thought we were getting one (seemingly) final classic Scorsese gangster movie. And we did, but that was merely the setting for what became a quasi-religious, reflective film. Told in retrospect by Robert DeNiro’s Frank Sheeran, we move sweepingly through decades of his involvement with organized crime, and, as it turns out, with his killing of Jimmy Hoffa, his dear friend.

As the film moves into its final third, we see age catching up with these characters, and Frank takes a more reflective tone in how he views how he spent his life. In the end, his friends have all passed on, most through violent acts, a scarce few of natural causes in their old age. Frank is left in a nursing home. His family is local, but rarely visit. The broken relationship with his daughter, Peggy, looms over the film. Even as a child, we see Peggy sheepish around her father. With her knowledge of his true vocation becoming more vivid as she grows, her silence becomes deafening through the film. She speaks only once in the entire film. Her lines simple, but indicting of her father’s deadly actions. She knows he killed her Uncle Jimmy. It’s that moment that Frank loses his daughter. He’ll spend the rest of his life trying to repair the unrepairable. In the end, Frank never admits or tells authorities of his transgressions, but we see moments of harrowing lament, regret, and futile attempt at redemption.

There’s also the element of metareflection insofar as we experience Scorsese reflecting on his own career via his classic gangster film. He’s made many through the decades, several of which involve the now elder actors who return to collaborate in The Irishman. There’s a finality to this film, as if Scorsese is sending off this type of film. And in doing so he tapers the violence that would have been more prevalent in his past films. He’s softer, quieter, and emotional here.

In Marriage Story, we see our two leads, Charlie and Nicole, recounting the aspects of their relationship and partner that they love. It’s full of sweet moments of their love and parentage with their young son. In a matter of moments, we have an intimate knowledge of this marriage.

And then our heart breaks.

This list is part of a therapy exercise that will lead to a divorce. The image that was created for us shattered. That reality is no longer. Yet this reflection from our two leads is the essence of the experience we have of them through the film. Charlie seems more tender to his soon-to-be ex-wife, while Nicole is more coarse and direct in her interactions with Charlie. This is not to pit us as the audience against Nicole. To choose a side misses the point of the film. We are instead meant to follow these two as they move into a significant moment of their lives, both as individuals and in their final months as a married couple. I’d argue that Nicole is not as rigid as she seems. She has, however, arrived at the closure of their marriage sooner than Charlie has. The movie works in reverse for these two characters. When we first meet Nicole, she’s ready for her new life divorced from Charlie. Charlie’s journey through the film is getting to the same point, and in the end, we seem him there. Yet it’s at that point where Charlie finally gets to know Nicole’s list of things she loves about him. She refused to share in the opening therapy session. Where Charlie began, Nicole ends. And where Nicole began, Charlie ends. Through the journey to arrive at this balance, we lean on how they view their history. Divorce is messy. But this one leaves me hopeful precisely because of how they reflect on one another.

If there’s a fun adventure that involves reflection, it’s surely in Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood. This film is many thing – a love for 50s/60s era Hollywood, a buddy film, a revenge plot against one of the most notorious cults in American history. Yet in the tales of Leonardo DiCaprio’s aging Hollywood star, Rick Dalton, we see a man grappling with his fading stardom. He was the it figure in an age of Hollywood that has already left. With his sidekick and stunt double Cliff by his side, Rick recounts his successes that he thought would last a lifetime, but have betrayed him as the world around him has found newer, younger stars to lead the new age of filmmaking.

Rick stands for so much of what the American dream means for people. He’s reached the heights of fame, or a contrived definition of success and riches. And it ultimately leaves him empty and alone, drunk and looking for meaning. As these fabricated definitions of success fade, Rick is just a man, flawed and usual like the rest of us.

If Once Upon a Time is the fun reflective film, Midsommar rests on the opposite end of this spectrum. This film is an agonizing, terrorizing experience. It’s a horror film, sure. But Ari Aster has managed to terrify audiences in broad daylight, with beautiful flowers and forests as the backdrop of a film I haven’t been able to stop thinking about. Here, a group of graduate students to Sweden with their friend to experience a festival. As it tuns out, this is a front for a pagan cult and their ritualistic practices that this group of friends become enveloped in. At the center of this is a young couple, Dani and Christian, who find their relationship strained. Dani has been through traumatic experience prior to the trip, and Christian is the less-than-ideal boyfriend who gaslights her through the film. As the story unfolds and the characters become further entangled in the deadly cultish practices, Dani becomes increasingly aware of Christian’s mistreatment of her and turns to the cult as a form of community. Somewhat unwillingly at first, Dani, the newly crowned “May Queen”, becomes more resolved about the state of her relationship through a series of reflections that lead to her clarity.

Other notable films of 2019 that I enjoyed: Ad Astra, Apollo 11, Booksmart, High Life, Hustlers, I Am Easy to Find, JoJo Rabbit, Joker, Us.